Our resources thrust participants into the heart of real-world scenarios, from crisis management in the UK during the Covid-19 pandemic to cross-party education reform in Brazil.

Many of our resources are available on The Case Centre distribution platform. Educators who are registered with the site can access free review copies of our case studies, teaching notes, and other materials.

To inquire about our other cases or background materials, please contact us at casecentre@bsg.ox.ac.uk.

Confronting corruption in Paraguay’s housing ministry

Soledad Núñez was offered the role of housing minister of Paraguay in October 2014, a ministry with a reputation as one of the most corrupt and ineffective public institutions in the country and for years, the ministry had failed to achieve its housing targets. Núñez knew that if she took on the role of minister, she would make powerful enemies, and her appointment would be opposed by many within the political establishment. But Núñez was determined to reform the ministry and fight the system of corruption that gripped it.

This case study follows Núñez during her difficult first year in office. Over the course of the year, Núñez created new regulations and processes, committed to transparency and improved the reputation of the organisation, all while increasing the delivery of homes sixfold. However, as 2015 came to an end, one of the high-ranking officials she had dismissed for his involvement in corruption returned to the ministry with a court order reinstating him. As news of his return spread through the offices, Núñez received word that some members of her staff were celebrating. Núñez was shocked: she had worked hard to change the culture of the ministry, but the official’s return seemed to be threatening to undo her work already. Núñez knew she would need to act quickly if she was to retain control of the situation.

- Analyse and differentiate between different types of power;

- Locate the distribution of power within an organisation and consider how to lead effectively within a polarised or corrupt organisation;

- Understand the role of leadership in supporting integrity and creating a values-based culture within an organisation.

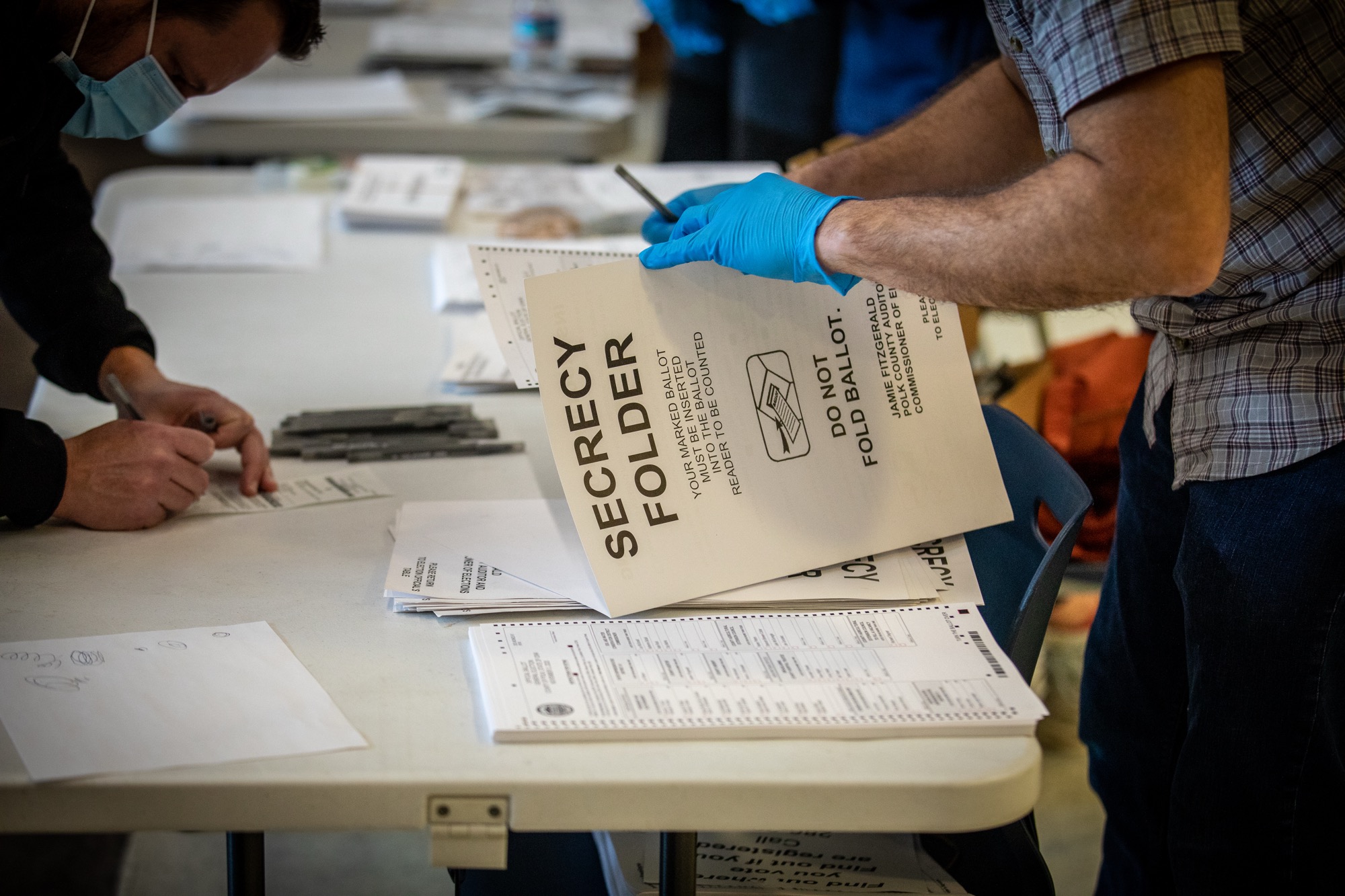

Defending democracy: cybersecurity and the 2020 US elections

It was 8 November 2020, and disinformation about the 2020 presidential election was spreading rapidly. Chris Krebs, Director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) within the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS), had to decide what his team should do.

The day before, Democrat nominee Joe Biden had been declared the winner of the election, besting incumbent President Donald Trump, a Republican. But Trump refused to concede, alleging widespread voting irregularities. CISA insisted that the elections were among the most secure in recent history: since 2017 CISA had been working to enhance security and resilience of America’s election system after alleged foreign interference in the 2016 elections. During that time, CISA was able to forge relationships with thousands of local and state officials around the country to improve security of country’s outdated election infrastructure, all while gaining bipartisan respect for its apolitical approach, even as the DHS became increasingly politicised.

Despite this progress, though, Trump and his allies were now questioning the validity of the election. Disinformation was growing rampant, and Trump allies were sharing a false story about a supercomputer flipping votes. Krebs had to decide how to respond to the false claim in a way that would preserve the public’s trust in the elections and CISA’s reputation.

- Explore how to lead an organisation with a highly technical mandate in the context of deep distrust;

- Understand key principles for managing a public institution in an age of deep polarisation.

Stop and search in London in the summer of Covid

In the summer of 2020, as the Covid-19 pandemic and associated lockdown heightened tensions between London’s Metropolitan Police Service (Met) and the communities they policed, the latest data was published on the Met’s use of stop and search. The reports showed that in May alone, during the strict lockdown, the Met had conducted 44,000 searches – an eight-year high – and searched Black Londoners at four times the rate of white Londoners. Stop and search was among the most contentious police powers in the UK. Many police leaders considered it a vital tool for detecting and preventing criminal activity, yet others, including some in the police, worried it was not used fairly, with Black and minority ethnic (BAME) individuals consistently searched at higher rates than their white counterparts. And while this racial disproportionality had endured for decades, it gained renewed visibility in 2020 as Black Lives Matter protests highlighted racial discrimination in policing. Commissioner Cressida Dick, the senior-most officer of the Met responsible for more than 30,000 officers, had to respond to the growing scrutiny around stop and search. This case puts students in her shoes to consider how she can build trust with minority ethnic communities while also maintaining the trust and confidence of the Met – an overwhelmingly white institution – as well as the wider public and multiple political structures.

- Examine approaches to building trust with multiple stakeholders;

- Develop action plans that incorporate diverse, and often conflicting, views of a number of stakeholders;

- Analyse the role of academic research, experiential evidence and other data in assessing policy effectiveness along social and political lines.