How connecting educators can take us further on foundational learning

When the Lemann Foundation Programme's South-South Programme started about a year ago, few of its fellows from Kenya and Pakistan knew each other. Now, they’re mobilising in coalitions to build consensus around priorities and push for improvements in education policy.

Taken from the ranks of academia, civil society, government, and the private sector in their home countries, the fellows from the South-South Programme had, in broad terms, a shared destination: a world in which each child can read, write, and count at the right age. This is commonly known as “foundational learning” – the building blocks of any educational pathway.

The South-South Programme, led by the Lemann Foundation Programme and partners with the aim of supporting education leaders from low- and middle-income countries, is timely. As many as 1.6 billion children worldwide were affected by school closures enacted to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. While some children had reasonably conducive set-ups to study at home, many did not, and those unable to read faced even greater challenges to self-study. The pandemic accentuated a ‘learning crisis’, requiring urgent action by governments, parents, and civil society. It is this pressing problem that the South-South Programme coalitions are aiming to address through policies that each coalition sets for themselves, ensuring these are appropriate to their country contexts. Other partners in the Programme are the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), the Lemann Center for Leadership & Equity in Education in Sobral, and the Lemann Foundation in Brazil.

It is too soon after the coalitions were set up to assess and measure the impact on learning outcomes, however changes in the number and richness of the connections between the fellows who compose them might be evident. This is what Filipe Recch, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Lemann Foundation Programme, recently set out to measure.

“If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together”.

Coalition building, often against the odds, is a core element of the Blavatnik School’s Master of Public Policy (MPP) programme. In short, whatever policy goal you want to achieve, you typically find an advantage in rallying groups aiming for the same thing, even if they don’t share the same background and may even espouse very different political views. Broad and diverse coalitions, especially those that can build productive, deliberative processes and achieve consensus of key issues, have a stronger chance of bringing about sustainable policy change than individuals going it alone.

John Mugo, Executive Director at Zizi Afrique, an NGO at the centre of coalition-building efforts in Kenya, captures this idea by referring to an African proverb: “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together”.

When the South-South Programme started, its fellows did not have much in common other than a passion for education. They were invited to join an intense year of activities, including virtual meetings in which they shared evidence and best practices, opportunities to develop their own leadership and technical capacity, and a week-long immersion trip to Brazil.

In Brazil, the fellows heard from Todos pela Educação, an NGO focused on improving public education in the country, and Movimento pela Base, a successful coalition formed to establish common curricular standards there. They also visited Sobral, a poor municipality in the northeastern state of Ceará, which managed to skyrocket in the Brazilian national ranking of education quality because it introduced, improved and sustained reforms in areas like school leadership, student evaluation and teacher training.

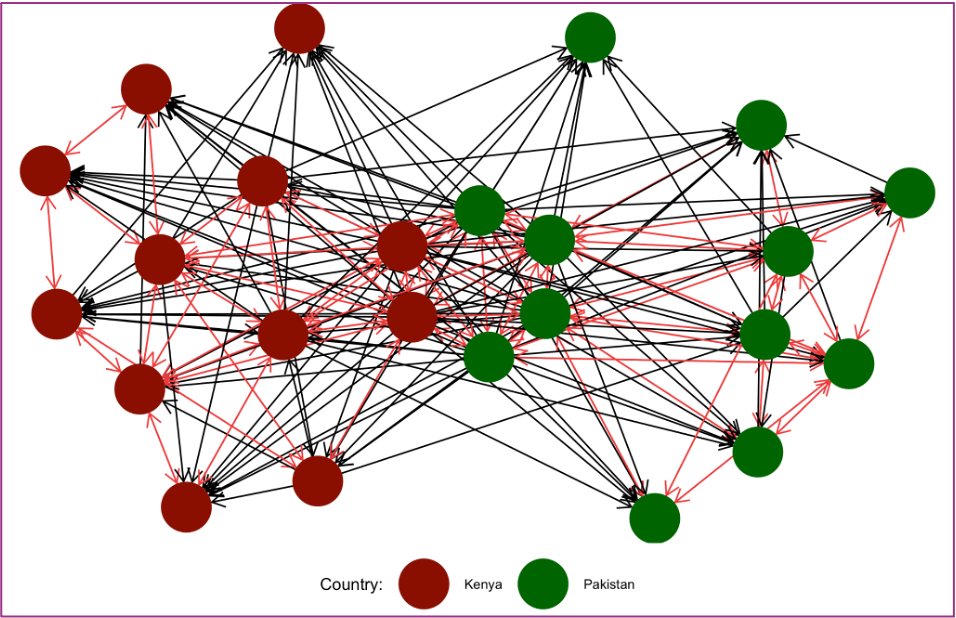

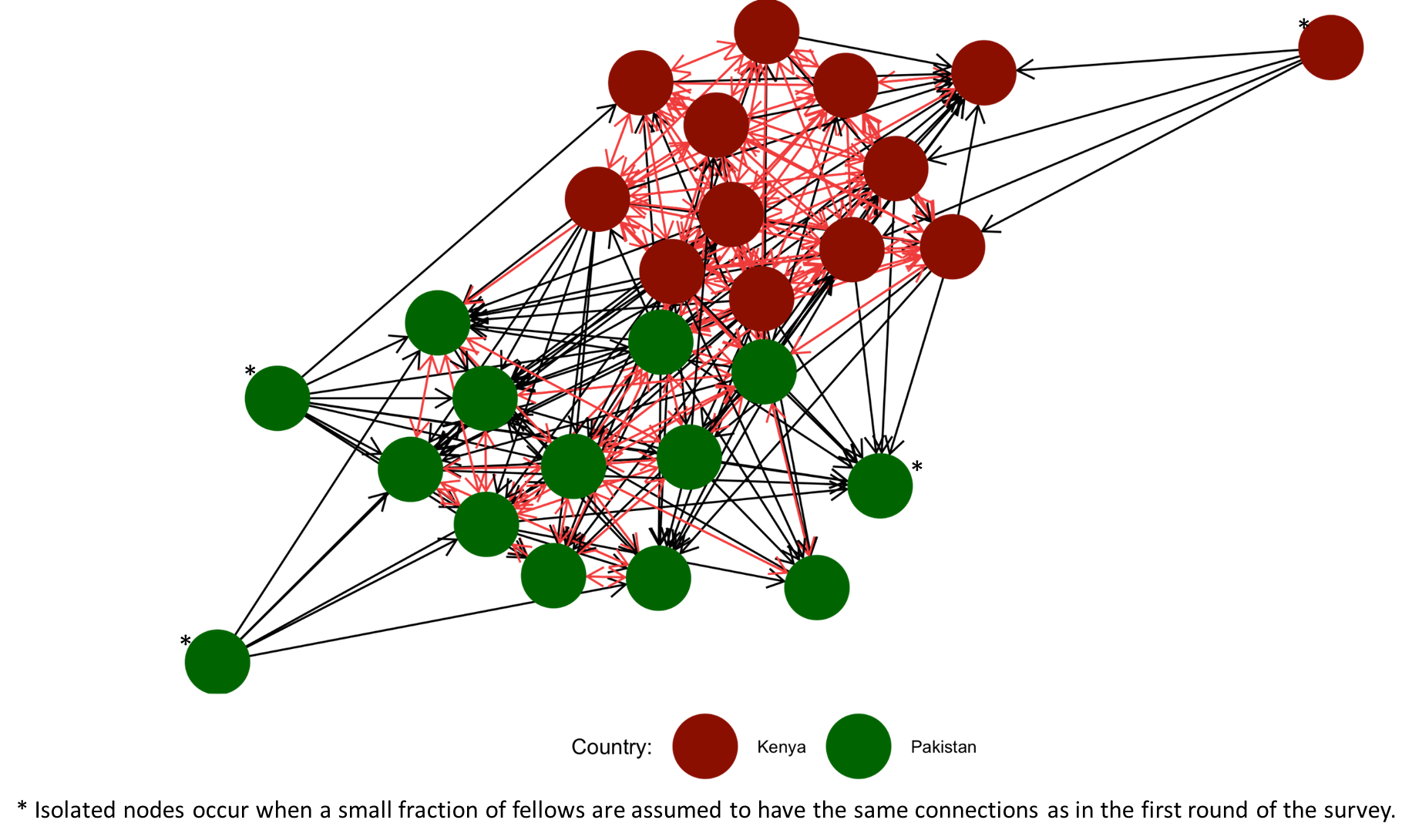

To assess the coalitions’ progress, Filipe conducted a social network analysis of the fellows’ relationships based on interviews conducted just before the main South-South Programme activities began and then just after this Programme concluded. The interval between the two surveys was seven months. The results can be seen in the diagrams below.

Each node in the diagram represents an individual fellow and their respective countries. Black arrows indicate connections mentioned by one fellow, specifically indicating that they have directly worked with the mentioned fellow. Red arrows represent reciprocal connections, where fellows mentioned each other separately, also implying a direct working relationship.

The images show the successful accomplishment of one of the South-South Programme's key goals. The ties between the fellows have become stronger, more diverse, and international in nature, with a focus on direct collaboration. The network within the group has become more tightly knit, and the connections are evenly distributed.

Prior to the Programme, most of these soon-to-be fellows had few connections while only a few of them had many connections. The situation has now reversed, with more fellows having multiple connections and fewer fellows having limited connections, all stemming from direct experiences of working together. The two isolated points you can see in the second graph are a result of a small minority of fellows who only responded to the first round of the survey, and thus were conservatively assumed to have only the same networks as before.

A parallel qualitative assessment, based on in-depth interviews[1], also revealed that fellows developed a more positive and optimistic outlook around educational reforms during the Programme, becoming more assertive in discussing those reforms and believing that change is possible. Fellows now focus more on collaboration and recognise that partnering with the right leaders (and not only politicians) can be key to bringing about change. Overall, participants in the Programme claim that they feel more prepared and confident in building networks around a shared goal and vision – and Filipe’s analysis showed that they use the term “coalitions” to describe this effort.

This shared vision is now being translated into real action. In Kenya, the coalition is seeking to turn Kirinyaga County into a positive point of reference for what is possible in terms of improving foundational learning (rather like Sobral), for which it already counts on the engagement of local stakeholders and national politicians. In Pakistan, the newly formed coalition is piloting an adaptive model in five communities to reform the education system of each of the country’s four provinces.

The ramifications of the South-South Programme are not limited to its participants and the groups they are impacting. A library of Global Public Goods developed by the Lemann Foundation Programme as part of the project was launched on 11 May. These materials, including case studies, discursive learning documents and podcasts, address major themes of education reform which are relevant to education policymakers in different developing countries.

The topics discussed in this library include the challenges of scaling up literacy and numeracy programs and managing relationships with international funders in Kenya, for example, and the use of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in the education sector in Pakistan. Collectively, these Global Public Goods are intended to foster careful and thorough deliberation with the coalitions, and strengthen them from the inside. And as Filipe’s analysis demonstrates, this seems to be happening already within the networks – as a sign that the long walk evoked by the African proverb is well underway.

[1] The survey was sent to all participants (30 in each round, so about 60 people received the survey with a response rate of around 90%) and there were 21 in-depth interviews (11 pre and 10 post programme).