Democracies in danger

By abruptly revoking the special, constitutionally protected status of Jammu and Kashmir, India has become the latest major democracy to act against a minority community for short-term political popularity. Kashmir will henceforth be ruled more directly from the government in New Delhi, and Hindu nationalists are thrilled. Carefully maintained constitutional arrangements are in tatters.

Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Boris Johnson has committed to leaving the European Union with or without a “backstop” protecting the border arrangements between British-ruled Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. His hardline position ignores the concerns of Northern Irish constituents entirely. It is geared toward rallying his pro-Brexit English base, even if that means threatening the fragile peace and prosperity in Ireland.

In the world’s other great democracy, President Donald Trump has upended America’s relationship with Mexico and other Central American neighbours, and rallied his base by repeatedly demonising Hispanics. The US Hispanic community is now paying a harsh price for such rhetoric, as evidenced by the massacre in El Paso, Texas, this month.

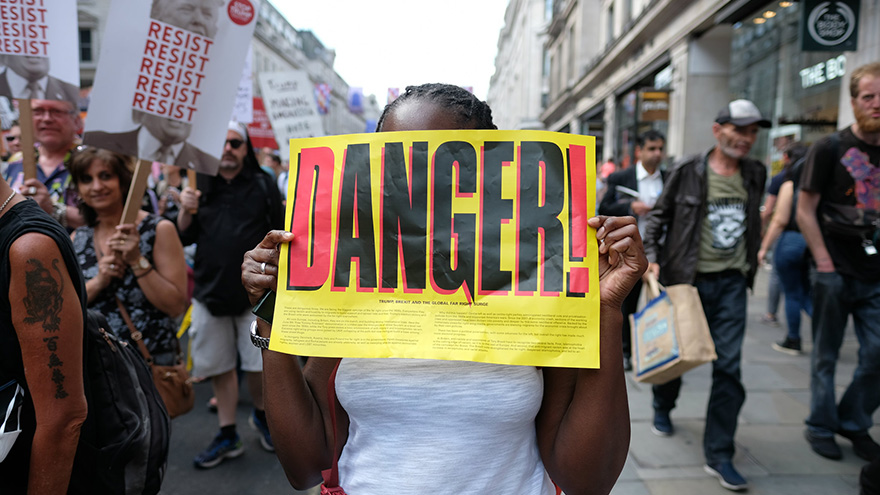

The shredding of longstanding protections for minority communities is part of a wider trend in democracies around the world. Three worrying features stand out. First, politicians are imperiling the “public square”, and the ability of citizens to argue, demonstrate and debate without the threat of violence. Political leaders are deepening social divisions by pitting an “us” against a “them” that includes foreigners, neighbors, immigrants, minorities, the press, “experts”, and “the elite”.

In India, rights groups have accused Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of creating a “climate of impunity” for angry mobs. In America, many believe Trump is doing the same, pointing, for example, to his racist tweets targeting four Democratic congresswomen of colour. During the Brexit referendum campaign in the UK, Facebook users were targeted with posts suggesting that staying in the EU would leave Britain vulnerable to receiving 76 million Turkish immigrants. One “Leave” ad showed a surly foreign man elbowing a tearful elderly white woman out of a hospital queue. A recent survey suggests that there has been a disturbing increase in racially motivated abuse, discrimination and attacks against ethnic-minority Britons.

Second, having won power through democratic elections, these leaders are seeking to weaken independent institutions and checks on executive power. For example, Trump invoked national-emergency powers to secure funding for his wall on the US border with Mexico. Johnson refuses to rule out suspending Parliament in order to deliver Brexit, while his chief adviser, Dominic Cummings, describes Britain’s permanent civil service as an “idea for the history books”. In India, a fellow BJP member has accused Modi’s government of “decimating” India’s constitutional institutions, including the Supreme Court, the national investigative agency, the central bank and the electoral commission.

Abusing emergency powers or executive orders, sidelining Parliament and government agencies, and weakening judicial independence and the “referees” that ensure political leaders play by the rules make it more likely that government decisions will not balance the interests of all citizens. These attacks on the independence of institutions leave minorities particularly vulnerable.

Finally, there is a risk that political power in the world’s democracies is becoming more personalized. Patronage, personal influence and favours are being used to create loyalty to the leader; and those who fall out of favor are being bullied from office or arbitrarily fired. Political leaders are also making ever-bolder attempts to cow the media and business community into silence, or to co-opt them by offering special privileges.

Indeed, nine officials have resigned or been dismissed from Trump’s cabinet since 2017, and the president regularly uses Twitter (and even presidential pardons) to reward loyalty or to bully those who fall into disfavour. In the UK, Brexiteers’ attacks on the UK civil servant leading negotiations with the EU became so aggressive as to elicit a highly unusual public statement from the acting cabinet secretary (telling those responsible that they should be “ashamed of themselves”). When Johnson became prime minister, 17 ministers were “purged” and new members of the government were required to pledge support for his goal of leaving the EU at the end of October.

The personalisation of power replaces formal and fair processes with discretionary decisions and favors. It erodes the democratic principle that all citizens – including the head of state – are subject to the rule of law, and that politicians exercise delegated power, not a personal fiat.

Many voters have expressed outrage at the actions of Modi, Johnson and Trump. But many other democracies are in trouble, too. Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro all stand accused of unconstitutional behavior. Nonetheless, each man continues to fan divisions, weaken independent institutions, and ignore open conflicts of interest, in many cases involving family members.

Shaming such leaders is unlikely to change their ways. They are all practised in blithely dismissing mistakes and shrugging off incendiary past statements, conflicts of interest, corruption allegations, lying and deception, and improper dealings.

Rather than relying on outrage, democrats around the world need to apply with rigour the rules that prevent the personalisation of power, while defending the institutions that protect individuals and minorities. Public officials should not be allowed to use their office to insulate themselves from accountability – through grants of immunity or presidential pardons to benefit friends and family members – or to hide evidence of their illegal behavior. We all must insist on clear and inviolable standards of transparency regarding the private interests of those in public office.

India, the UK and America are each “model” democracies: India is the largest, Britain has the “Westminster model”, and America has an extraordinary constitution. In each of these great democracies, minorities are under attack, as are the conventions that restrain executive power. Citizens in each country need to understand that if they do not defend the institutions that protect minorities today, they themselves may come under attack tomorrow.

This piece was originally published by Project Syndicate on 12 August 2019.

Ngaire Woods is the founding Dean of the Blavatnik School of Government and Professor of Global Economic Governance at the University of Oxford.