COVID-19 public information campaigns in Chinese provinces

Governments have been communicating with the public about the COVID-19 pandemic in a variety of ways. In China, provincial-level jurisdictions have recorded similarities in responsiveness and significant variation in format.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries have used traditional media, social media, websites and direct messaging to publicise information on COVID-19 and corresponding government policies.

While the content of public information campaigns has received some academic attention, their speed and format have not been widely analysed. I looked at these dimensions using data on public COVID-19 information campaigns in Chinese provincial-level jurisdictions, collected by the China subnational team working on the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, which includes policies issued by national, provincial and lower-level local governments. The data shows two macro patterns: a) with respect to the speed of action taken by governments to install coordinated public information campaigns, Chinese provinces have shown little variation; b) significant regional variations exist for the method communication.

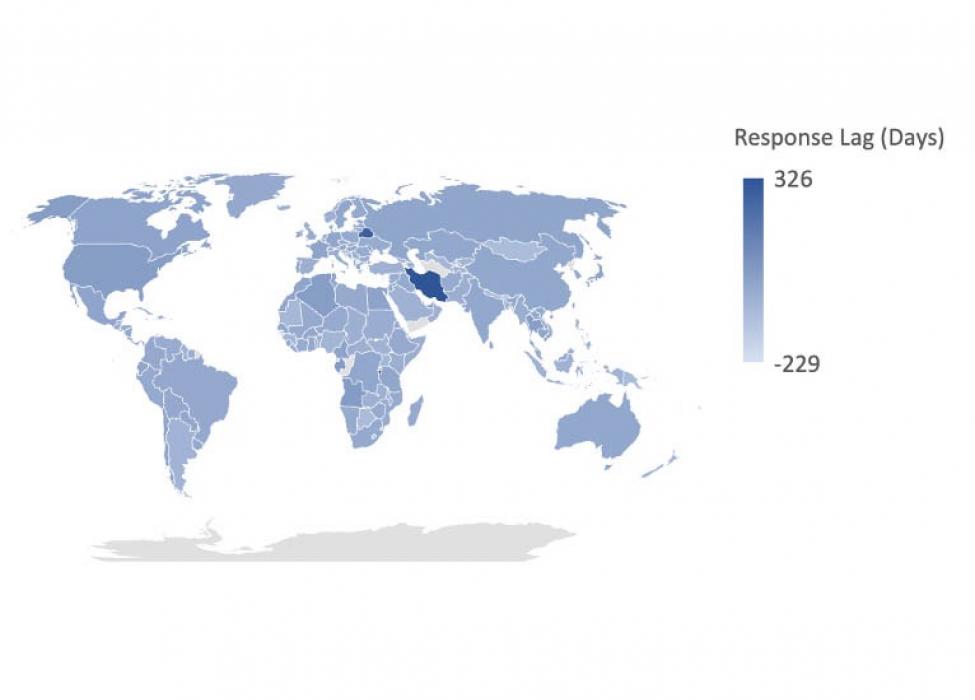

Data from the OxCGRT shows that the timing of introducing public information campaigns varies greatly across countries. Globally, on average, nationwide coordinated public information campaigns were introduced 12.07 days before a country recorded its 10th confirmed case; however, some countries stand out. For instance, in the Solomon Islands, coordinated public campaigns preceded the 10th case by 229 days, while in Iran they lagged by 326 days. Chinese provincial-level jurisdictions are quicker to respond on average and with little variation. Coordinated campaigns started 2.34 days before the 10th case on average, ranging from 8 days before or 4 days after the 10th case (please note that Tibet is excluded from this analysis because the autonomous region has ever recorded only 1 confirmed case). All Chinese provincial governments started coordinated public campaigns no later than 31st January.

Figure 1 - Response lags between the 10th case and the start of national coordinated campaigns. Positive values indicate the Campaign started later than the 10th Case

The speed of the response is because most provinces launched their daily briefing programs on the day after their first confirmed case. Daily briefings are issued by the governments at all levels, including the national government. They are published every day regardless of whether there are new cases, a policy called “zero-report”, meaning the consecutive daily report must be made even if the place has zero new cases. Daily briefings, as well as the zero-report policy, have been implemented since the 2003 SARS pandemic (see sources 1, 2 and 3), and were also in place during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

When the number of confirmed cases is small, some regions (e.g. Chengdu city of Sichuan Province) publish a detailed, anonymised mobility trajectory of every new patient. When a cluster of transmission has occurred and then controlled, some regions (e.g. Liaoning Province) report whether any subsequent case is associated with the cluster; in some regions (e.g. Ningxia Province), the briefing includes the number of consecutive days without new confirmed cases. Sometimes briefings include the variants detected (e.g. Beijing Municipality). Most briefings specify whether the cases are local or internationally imported. Daily briefings are usually released through press conferences and posted on the official website of the local Health Commission, social media accounts of local governments, or official mobile Apps. This information has also been posted via third-party commercial platforms (such as the "Dr Dingxiang" website/APP – a leading digital health service provider in China).

Aside from the daily updates, the national and provincial governments have launched comprehensive information campaigns since late January 2020, covering areas such as health advice, containment and travel rules, public health measures and economic support information. In addition to traditional avenues such as broadcasting and leaflet distribution, governments used extra measures to reach remote audiences. Debunking misinformation has also been a concern for both national and regional governments.

Several provinces have set up online misinformation debunking portals. For instance, Chongqing Municipality created a dedicated webpage to refute rumours and misinformation. Shiyan City in Hubei Province publishes fact-checking reports by local media and trusted commercial partners such as Dr Dingxiang. Regional governments often remind businesses that they would face legal consequences if they profit from misinformation. In some cases where commercial advertisements exaggerated the effects of disinfectants, PPE, supplements and Chinese traditional medicine in “preventing” or “treating” COVID-19, governments, such as Beijing Municipality and Nanjing City, Jiangsu Province, resorted to the Anti-Unfair Competition Law, emphasising that companies advertising false or exaggerated anti-COVID-19 effects are liable to fines of up to two million yuan and their business licenses could be revoked.

Publicity campaigns reflect efforts to engage a wider audience. Beijing Municipality made an animated video, while Guiyang City produced rap songs to publicise COVID-19 policy enforcement measures, appealing to the younger generation. Some regions initiated creative formats to disseminate COVID-19 information in both Chinese and ethnic minority languages, to improve access for non-Chinese speakers. For instance, Lhasa created a Tibetan-Chinese bilingual drama entitled Fight Against COVID. Meanwhile, Jiangxi Province and many jurisdictions in Liaoning Province published open letters to persuade citizens to follow government policies.

Existing evidence suggests that using the internet as the main method of communication during the pandemic is biased towards urban residents, since the technology divide between rural and urban areas remains severe. To address this, Guizhou Province, Liaoning Province, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and many other places used rural "Big Speakers" (public broadcasting loudspeakers in villages) to aid their information campaign. For example, the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region employed a comedy radio drama. The Kustek Town in Xinjiang Autonomous Region organised a "Horseback Publicity Service Team" to help remote herders purchase supplies, while disseminating COVID-19 prevention and control information. The Jinnong (“golden agriculture”) telephone Hotline of Liaoning Province, a hotline that normally offers agricultural information, has also added an audio guide that advocates for mask-wearing. At the national level, the State Council designed a version of a comic COVID-19 brochure specifically for rural settings.

Many governments in regions with large ethnic minority populations have translated Chinese materials into minority languages. For instance, Guizhou Province disseminated multilingual audios, while the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region translated pandemic control brochures into Mongolian, and the Sichuan Province into Tibetan (Figure 3).

Figure 3. COVID-19 information brochure in Tibetan

Facing the unprecedented challenges posed to public governance during COVID-19 pandemic, the battle between scientific information and misinformation is more relevant than ever. Learning some of the strategies used by the Chinese government at a national and provincial level can be helpful in expanding public information campaigns in other countries.

Yanying Lin studies philosophy and psychology at the University of Oxford. In 2020, she founded a grassroot volunteer group in China with a few friends and delivered $70,000 worth of PPE to hospitals in the pandemic centre. Her current work with the China subnational team of the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker includes coding and standardising coding practice.

The author would like to sincerely thank Dr Yuxi Zhang and Martina Di Folco for their invaluable support and guidance. Many thanks also to Ziyue Chen for extensive information on Guizhou’s policy, and to Ruiyang Feng and Shaakirah Sivardeen for their very helpful suggestions.