£1m ‘obesity’ deal with Coke a no-no, BoJo.

Estimated reading time: 4 Minutes

Last week brought us the news that London Mayor, Boris Johnson, has teamed up with Coca-Cola to ‘tackle obesity’. They will match-fund £500,000 from the Mayor to encourage more people to get active. This is part of a trend of Coke sponsoring physical activity projects around the world, such as the ‘Happiness Cycle’ partnership with Bicycle Network Victoria in Australia.

‘What’s wrong with that?’ you might think. ‘Good old Coke, doing their bit.’ Well, exactly what’s wrong is highlighted by the work I’m doing for my summer placement at the Obesity Policy Coalition (OPC) in Melbourne.

The OPC is concerned by growing levels of obesity in Australia, and we know that sugary drinks contribute significantly to this trend. A UK survey undertaken by Action on Sugar found that 79% of 232 sugar-sweetened drinks contained six or more teaspoons of sugar per 330ml can. This is more sugar than the World Health Organisation recommends an adult should consume in one day.

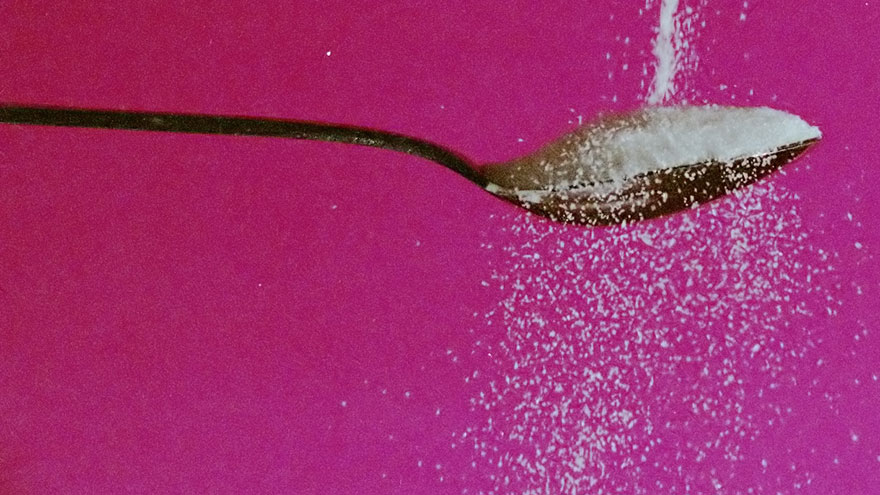

[caption id="attachment_7387" align="alignnone" width="880"] Image source: morgueFile[/caption]

Image source: morgueFile[/caption]

These ‘sugar-sweetened beverages’ contribute significantly to obesity - it is estimated that one can of soft drink per day could lead to a 6.75kg weight gain in one year - while offering no other nutritional value. By undertaking corporate social responsibility projects to ‘tackle obesity’ Coca-Cola is avoiding the real issue – its products are fuelling the obesity epidemic. In both the UK and Australia, more than 60 per cent of adults are overweight or obese. The figure for children is 1 in 4.

This represents a huge public health threat because obesity is one of the biggest risk factors for illnesses like heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. In Australia, dietary risks and high body-mass index have overtaken smoking as the biggest threats to the country’s health, according to the Global Burden of Disease study. There is a risk that, if current trends continue, there will be 1.75 million deaths at ages 20+ years between 2011 and 2050, with an average loss of 12 years of life for each Australian who dies before the age of 75. There is also a risk that today’s children will die younger than their parents’ generation.

And that’s not all. The economic costs of obesity to society are astronomical. The National Preventative Health Taskforce stated that the overall cost of obesity to Australian society and governments in 2008 was $58.2billion AUD. It’s a similar story in other developed nations. But policy measures have not kept pace with the health and economic threats posed. If obesity rates could be halted between 2011 and 2050, half a million lives could be saved in Australia alone. But while Australia leads the world in tobacco control efforts, followed closely by the UK, neither country has done very much to tackle the obesity epidemic.

So what can be done? Restricting junk food advertising to children, taxing unhealthy foods to subsidise fresh fruit and veg, introducing clear front-of-pack labelling for food and drink with warnings on unhealthy products, delivering social marketing campaigns to warn people of the dangers of an unhealthy diet and encouraging healthy alternatives to fizzy drinks like water and reduced-fat milk, are all evidence-based measures that could make a big difference. But they are unlikely to be implemented while Coke cosies up to our elected representatives and convinces them that they do not need to act.

Policymakers in Australia and the UK have largely accepted that tobacco companies should have no role in shaping public health policy. The World Health Organisation states in its Global Strategy for Non Communicable Diseases that,

The waters are muddied when it comes to obesity, because while there is no safe level at which to smoke, we all have to eat. This makes the public health messages more nuanced and, therefore, more difficult to get across. Food and drink companies have a legitimate seat at the table with government on some issues. But policymakers need to know where to draw the line.

At first glance, £1m for physical activity may seem like a sweet deal. But Coca-Cola’s involvement means it’s a distraction from the evidence-based policies that will really make a difference to obesity rates, and save lives. And that, BoJo, makes teaming up with Coke a big, fat no-no.

Heather Walker is a BSG MPP student currently undertaking her summer project at the Obesity Policy Coalition based at Cancer Council Victoria.

‘What’s wrong with that?’ you might think. ‘Good old Coke, doing their bit.’ Well, exactly what’s wrong is highlighted by the work I’m doing for my summer placement at the Obesity Policy Coalition (OPC) in Melbourne.

The OPC is concerned by growing levels of obesity in Australia, and we know that sugary drinks contribute significantly to this trend. A UK survey undertaken by Action on Sugar found that 79% of 232 sugar-sweetened drinks contained six or more teaspoons of sugar per 330ml can. This is more sugar than the World Health Organisation recommends an adult should consume in one day.

[caption id="attachment_7387" align="alignnone" width="880"]

Image source: morgueFile[/caption]

Image source: morgueFile[/caption]These ‘sugar-sweetened beverages’ contribute significantly to obesity - it is estimated that one can of soft drink per day could lead to a 6.75kg weight gain in one year - while offering no other nutritional value. By undertaking corporate social responsibility projects to ‘tackle obesity’ Coca-Cola is avoiding the real issue – its products are fuelling the obesity epidemic. In both the UK and Australia, more than 60 per cent of adults are overweight or obese. The figure for children is 1 in 4.

This represents a huge public health threat because obesity is one of the biggest risk factors for illnesses like heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. In Australia, dietary risks and high body-mass index have overtaken smoking as the biggest threats to the country’s health, according to the Global Burden of Disease study. There is a risk that, if current trends continue, there will be 1.75 million deaths at ages 20+ years between 2011 and 2050, with an average loss of 12 years of life for each Australian who dies before the age of 75. There is also a risk that today’s children will die younger than their parents’ generation.

And that’s not all. The economic costs of obesity to society are astronomical. The National Preventative Health Taskforce stated that the overall cost of obesity to Australian society and governments in 2008 was $58.2billion AUD. It’s a similar story in other developed nations. But policy measures have not kept pace with the health and economic threats posed. If obesity rates could be halted between 2011 and 2050, half a million lives could be saved in Australia alone. But while Australia leads the world in tobacco control efforts, followed closely by the UK, neither country has done very much to tackle the obesity epidemic.

So what can be done? Restricting junk food advertising to children, taxing unhealthy foods to subsidise fresh fruit and veg, introducing clear front-of-pack labelling for food and drink with warnings on unhealthy products, delivering social marketing campaigns to warn people of the dangers of an unhealthy diet and encouraging healthy alternatives to fizzy drinks like water and reduced-fat milk, are all evidence-based measures that could make a big difference. But they are unlikely to be implemented while Coke cosies up to our elected representatives and convinces them that they do not need to act.

Policymakers in Australia and the UK have largely accepted that tobacco companies should have no role in shaping public health policy. The World Health Organisation states in its Global Strategy for Non Communicable Diseases that,

“Public health policies, strategies and multisectoral action for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases must be protected from undue influence by any form of vested interest.”

The waters are muddied when it comes to obesity, because while there is no safe level at which to smoke, we all have to eat. This makes the public health messages more nuanced and, therefore, more difficult to get across. Food and drink companies have a legitimate seat at the table with government on some issues. But policymakers need to know where to draw the line.

At first glance, £1m for physical activity may seem like a sweet deal. But Coca-Cola’s involvement means it’s a distraction from the evidence-based policies that will really make a difference to obesity rates, and save lives. And that, BoJo, makes teaming up with Coke a big, fat no-no.

Heather Walker is a BSG MPP student currently undertaking her summer project at the Obesity Policy Coalition based at Cancer Council Victoria.