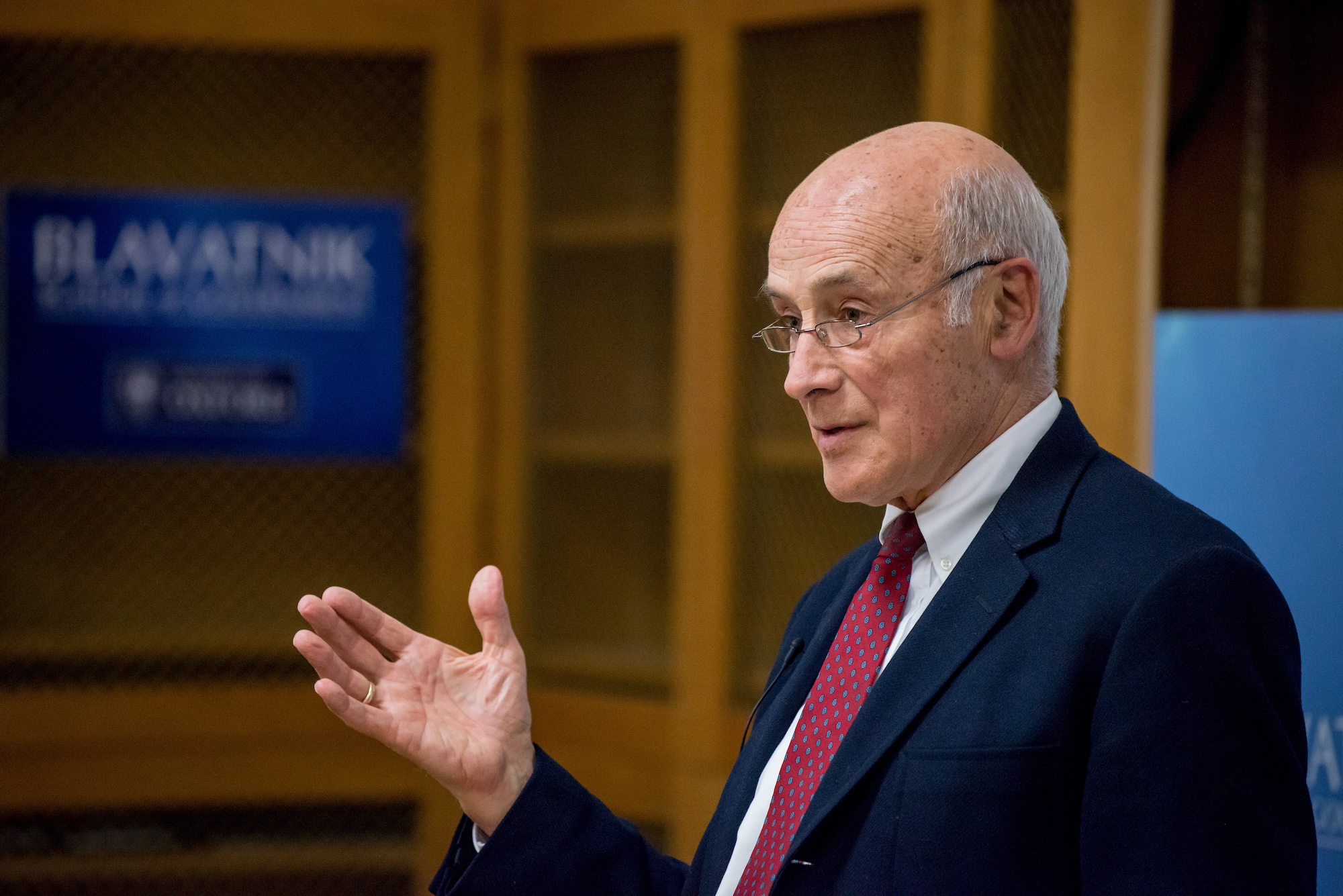

In Memory of Joseph S Nye

Melita Leousi, a DPhil in Public Policy (2015) student at the Blavatnik School of Government and Nuffield College, University of Oxford, writes following the passing of Joe Nye.

For the whole earth is the sepulchre of famous men; not only are they commemorated by columns and inscriptions in their own country, but in foreign lands there dwells also an unwritten memorial of them, graven not on stone but in the hearts of men.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, “Funeral Oration of Pericles” (trans. Benjamin Jowett, Clarendon Press, 1900)

Joseph Nye reshaped how the world thinks about power — and how power ought to be practiced. A scholar of rare clarity and a public thinker of enduring influence, he gave political life a vocabulary rooted not just in force or interest, but in judgment and responsibility.

His ideas — soft power, smart power, and, with his dear friend and long-time academic partner Professor Robert O. Keohane, complex interdependence — are now part of the intellectual fabric of international relations. But what set him apart was never only conceptual originality. It was his insistence that global affairs must still be guided by ethical judgment. That leadership is not merely about results, but about the kind of person — and the kind of society — one becomes in shaping them.

Joe offered this not as sentiment, but as discipline.

Joe Nye’s influence reached far and wide — students, ministers, diplomats, deans — across countries and generations. Those who encountered him rarely forgot the experience. He had that rare quality of brilliance without self-importance. He listened carefully, asked questions that mattered, and encouraged reflection over reaction. There was an unmistakable steadiness to him: calm in the face of noise, clear in moments of uncertainty, always oriented toward the long arc.

I was fortunate to know him not only through his writing, but through his mentorship. Working with him on the Future of Government Global Agenda Council at the World Economic Forum, I saw firsthand how generously he gave his time, how steadily he guided without ever imposing, and how seriously he took the development of others. Joe Nye, together with Professor Woods, convinced me to pursue a doctorate. Joe read my Oxford DPhil application, advised me on the architecture of my doctoral work, introduced me to Professor Robert O. Keohane, and offered clarity at moments when decisions mattered most. His advice was never prescriptive — but it always helped me find my own compass.

In all the Davos meetings I attended alongside Joe, as well as at the Global Agenda Summits in Dubai (now the Global Future Summits), we would be stopped every few steps by former students, global leaders, and decision-makers — each wanting a moment with him. It was striking how many sought him out not for show, but for substance — a word of advice, a shared memory, a thank you. That steady stream of recognition was a quiet testament to the depth and reach of his impact.

The day Joe passed, I was in Oxford, attending the Kyoto Prize laureates’ panel at Rhodes House — the place where he began his academic journey as a Rhodes Scholar. Presiding over the event was Professor Ngaire Woods, my DPhil Supervisor at Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government, whose mentorship, like Joe’s, profoundly shaped my path. As I was leaving Rhodes House, I once more looked up at the ceiling and read the inscription:

ΤΟ ΑΝΘΡΩΠΙΝΟ ΑΓΑΘΟΝ ΨΥΧΗΣ ΕΝΕΡΓΕΙΑ ΓΙΝΕΤΑΙ ΚΑΤ᾽ ΑΡΕΤΗΝ ΕΙ ΔΕ ΠΛΕΙΟΥΣ ΑΙ ΑΙΡΕΤΑΙ ΚΑΤΑ ΤΗΝ ΑΡΙΣΤΗΝ ΚΑΙ ΤΕΛΕΙΟΤΑΤΗΝ ΕΤΙ ΔΕΝ ΒΙΩΙ ΤΕΛΕΙΩΙ

The human good is the activity of the soul in accordance with virtue; and if there are many virtues, then in accordance with the best and most complete one — and in a complete life.

This is a paraphrased passage from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, expressing the idea that the highest human fulfillment comes from living a life of virtuous action — especially when that action aligns with the highest form of virtue and is sustained throughout a full life.

At the time, I simply thought of how precisely those words reflected the man Joe is — how clearly they matched the life he shaped through scholarship, through public service, the commitment to his beloved wife Molly, their three sons, and nine grandchildren, and through the care he offered to others. A day and a half later, I learned Joe had passed. And it felt, then, like something profound had come full circle — a moment unlooked for, yet unforgettable.

We last spoke on April 23. Joe mentioned, with his usual energy, his upcoming annual trip to Oxford, scheduled for May 20 — this time for a debate at the Oxford Union. Even in that brief exchange, his clarity and generosity were undiminished. I will forever be grateful to Joe.

Farewell, Joseph S Nye. You and your life’s work will never be forgotten.