Design, not decay in government buildings

Estimated reading time: 4 Minutes

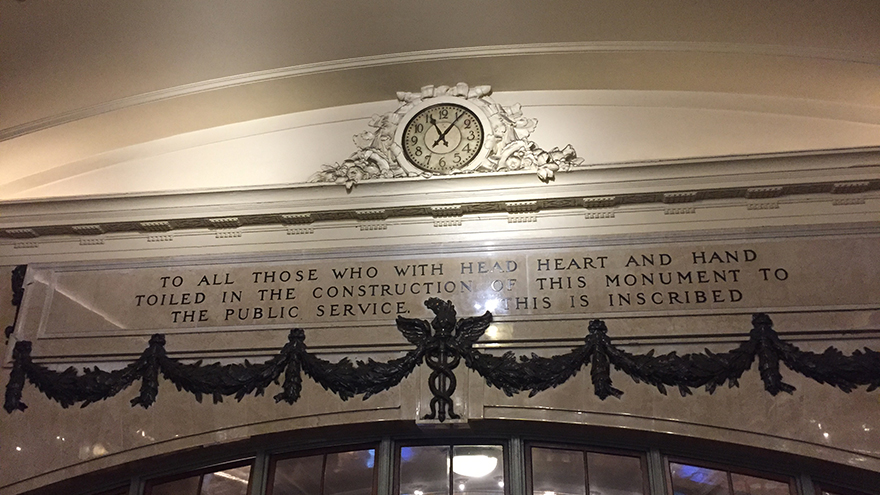

As a fresh faced civil servant on her first posting to Bangalore in 2003, it thrilled me to bits to read the motivational etching on the Vidhana Soudha, Bengaluru’s postcard monument that houses the State Legislature. It says in native Kannada first: Sarkarada kelasa Devara Kelasa and below it, the English translation: “Government work is God’s work”. Many years later, standing below a sepia-tinged clock at New York’s Grand Central Station entrance, I read the following words (now ridden with cynicism): “To all those who with head, heart and hand toiled in the construction of this monument to the public service, this is inscribed”.

[caption id="attachment_8999" align="alignnone" width="880"] New York's Central Station. Photo by author.[/caption]

New York's Central Station. Photo by author.[/caption]

On that same trip, across the statue of a stoic Thomas Jefferson in the Virginia Capitol Building at Richmond, I read that “the most sacred duties of a government is to do equal and impartial justice to its citizens”.

The common thread in these public buildings highlighted to me that the design and architecture in civil spaces as a reflection of the ideals of government and good governance has not probably received the attention it deserves.

First, it serves the goal-setting purpose of hard work, selflessness, and community service. Second, it is motivating for the scores of people in the government, who deal with systemic sclerosis and poor pay, to be publicly acknowledged. Third, the citizens feel a sense of pride, participation and positive presence of the government.

What is the scope of art and aesthetics in government and governance? Art and design communicate. No piece of work is ever mute; it speaks and conveys meanings within a context. This is where the architectural design of a government building assumes importance as it instantly communicates to anyone who enters, stays or even walks past briefly.

The administrative buildings of the labyrinthine North Block and South Block in New Delhi evoke a sense of grandeur and awe as it flanks the President’s House or the Rashtrapati Bhavan. Much thought went into its construction and needless to say, it sought to communicate the might and superiority of the British Empire to the Indian subcontinent.

While careful design and execution goes in constructing residences for heads of the state and parliaments, the same cannot be said for the small government offices that house the various departments away from the capital cities.

My experience in India has not been very encouraging. Often in obscure locations, government buildings are decrepit structures with little money or initiative for upkeep and maintenance. Most citizens pray they never have to enter it. Officials working in them have no choice but to make do with dilapidation and decay. I have plucked out banyan saplings, whose roots seek and find moisture from leaking pipes in what is their moment of Biblical fulfilment. Where they have been left alone, in a fit of apathy or conservationism, they have sent their aerial roots bursting through concrete and crumbled buildings without guilt.

The visual impact that a building (in both its aesthetics and upkeep) has on the onlookers can’t be underestimated. Smart, efficient buildings fill the users with a sense of pride and belonging. The message that an ill-maintained government structure sends to its citizens influences their perception of governance of the land itself: apathetic and inefficient to the point of not being able to keep its own house in order. When governments cite lack of funds for maintaining their spaces, people then wonder about the efficiency and purpose of tax revenue.

I spent much of Michaelmas (Oxford’s autumn term) with my classmates (MPP class of 2015) traipsing under the watchful eyes of the gargoyles on University buildings across Oxford and the temporary premises of the Blavatnik School on Merton Street. The absence of a proper space that was defined for us, created confusion and kept us from settling in. But when the new building at Radcliffe Observatory Quarter was open, our joy knew no bounds – state-of-the-art classrooms that were energy-efficient, lovely flights of stairs up and down an imposing circular structure that sat in the heart of Oxford like a vivacious, young thing amidst yellowing spires. There was something so refreshingly modern and smart about the new School of Government building that it seemed to embody what the School stood for in more ways than one.

There is a case for improving the architecture and design of government houses. There is a need to study this aspect more carefully and how the change in perception of the efficacy and efficiency of governments could be channelled through their buildings.

Susan Thomas is an alumna of the Blavatnik School of Government (MPP Class of 2015). She has been with the Government of India since 2001 as part of the Indian Revenue Service (IRS) and works presently as the Additional Commissioner of Income Tax at Bengaluru. Views expressed are purely personal.

[caption id="attachment_8999" align="alignnone" width="880"]

New York's Central Station. Photo by author.[/caption]

New York's Central Station. Photo by author.[/caption]On that same trip, across the statue of a stoic Thomas Jefferson in the Virginia Capitol Building at Richmond, I read that “the most sacred duties of a government is to do equal and impartial justice to its citizens”.

The common thread in these public buildings highlighted to me that the design and architecture in civil spaces as a reflection of the ideals of government and good governance has not probably received the attention it deserves.

First, it serves the goal-setting purpose of hard work, selflessness, and community service. Second, it is motivating for the scores of people in the government, who deal with systemic sclerosis and poor pay, to be publicly acknowledged. Third, the citizens feel a sense of pride, participation and positive presence of the government.

What is the scope of art and aesthetics in government and governance? Art and design communicate. No piece of work is ever mute; it speaks and conveys meanings within a context. This is where the architectural design of a government building assumes importance as it instantly communicates to anyone who enters, stays or even walks past briefly.

The administrative buildings of the labyrinthine North Block and South Block in New Delhi evoke a sense of grandeur and awe as it flanks the President’s House or the Rashtrapati Bhavan. Much thought went into its construction and needless to say, it sought to communicate the might and superiority of the British Empire to the Indian subcontinent.

While careful design and execution goes in constructing residences for heads of the state and parliaments, the same cannot be said for the small government offices that house the various departments away from the capital cities.

My experience in India has not been very encouraging. Often in obscure locations, government buildings are decrepit structures with little money or initiative for upkeep and maintenance. Most citizens pray they never have to enter it. Officials working in them have no choice but to make do with dilapidation and decay. I have plucked out banyan saplings, whose roots seek and find moisture from leaking pipes in what is their moment of Biblical fulfilment. Where they have been left alone, in a fit of apathy or conservationism, they have sent their aerial roots bursting through concrete and crumbled buildings without guilt.

The visual impact that a building (in both its aesthetics and upkeep) has on the onlookers can’t be underestimated. Smart, efficient buildings fill the users with a sense of pride and belonging. The message that an ill-maintained government structure sends to its citizens influences their perception of governance of the land itself: apathetic and inefficient to the point of not being able to keep its own house in order. When governments cite lack of funds for maintaining their spaces, people then wonder about the efficiency and purpose of tax revenue.

I spent much of Michaelmas (Oxford’s autumn term) with my classmates (MPP class of 2015) traipsing under the watchful eyes of the gargoyles on University buildings across Oxford and the temporary premises of the Blavatnik School on Merton Street. The absence of a proper space that was defined for us, created confusion and kept us from settling in. But when the new building at Radcliffe Observatory Quarter was open, our joy knew no bounds – state-of-the-art classrooms that were energy-efficient, lovely flights of stairs up and down an imposing circular structure that sat in the heart of Oxford like a vivacious, young thing amidst yellowing spires. There was something so refreshingly modern and smart about the new School of Government building that it seemed to embody what the School stood for in more ways than one.

There is a case for improving the architecture and design of government houses. There is a need to study this aspect more carefully and how the change in perception of the efficacy and efficiency of governments could be channelled through their buildings.

More than ever, we need to ask the question of why some governments fail to attract and retain talent as employers. The government business, God’s work or otherwise, comes with its own decorum and codes, and probably cannot offer sleep suites and fancy team retreats like the corporate firms. But nothing stops them from building houses that capture the imagination of their citizens and pay an occasional tribute to the scores of people engaged in public service. Policy formulation cannot after all be plagued by poor design.

Susan Thomas is an alumna of the Blavatnik School of Government (MPP Class of 2015). She has been with the Government of India since 2001 as part of the Indian Revenue Service (IRS) and works presently as the Additional Commissioner of Income Tax at Bengaluru. Views expressed are purely personal.